When business owners talk about selling their company, they almost always lead with one number: the purchase price. “We just agreed to sell for $10 million.” I hear that often and, honestly, I get it. That’s what gets the attention, the headlines, the celebratory texts from family and employees.

But here’s what most founders don’t realize until later in the process. The purchase price is not the same thing as the money that ends up in your bank account when the deal closes. Transaction costs are real. They are unavoidable. And if you don’t understand them going in, they can feel like a shock at the worst possible time. The closer you get to closing, the more you care about this.

That’s why, in this post, I want to walk you through the most common transaction fees sellers incur in a sell-side M&A deal, using a $10 million sale as our reference point.* These aren’t theoretical line items. These are the costs I see again and again as I work with founders doing real deals.

And if you want to come out of a sale feeling good about the outcome, it helps to know what’s coming.

It’s natural to focus on valuation. I do it myself with my clients every day. We talk about multiples and EBITDA and strategic value. Buyers care about that, and sellers should too. But sellers ultimately need to focus on the final number after all the expenses have been taken into account.

Because while a $10 million headline number sounds great, once you strip out the fees and costs that are part of closing a company sale, your net after all transaction costs starts looking different.

So, let’s take a look at the most common transaction costs:

1. Your M&A Advisor’s Fee Is Usually the Biggest Cost

The largest single cost in most deals is the M&A advisor or investment banker success fee. On a $10 million deal with a 3 percent success fee, that’s roughly $300,000 coming off the top at closing. Sometimes there is a credit for earlier preparation fees, sometimes there isn’t.

For many founders, that number feels large, or even painful, when they see it in the final settlement statement. But it’s worth remembering that this fee is tied to results. Your advisor created the competitive process, managed multiple buyers, protected leverage, navigated terms, and got you to a signed contract and a close date. Without that work, especially in a competitive or complex process, you may not have gotten the same price, the same protections, and the same terms.

Is it expensive? Yes. Does it create value? Almost always.

2. Legal Fees Are Real, But Not as Large as Your Fear

Another cost sellers almost always pay is legal fees for their counsel. On a $10 million transaction with a reasonable buyer and a relatively standard purchase agreement, legal fees are often in the $35,000 to $60,000 range.

People worry about legal costs early in the process, but what drives costs is not the size of the deal. Legal expenses rise because of deal friction. If you and the buyer are at odds over every provision, if the purchase agreement becomes an arena for philosophical battles rather than straightforward terms, or if indemnity, escrow, and working capital provisions become proxies for value transfers, the clock runs up and your bill goes up with it. If you have efficient, experienced counsel and a rational counterparty, legal fees stay relatively modest.

Plan for legal counsel to hold your hand through this, but also understand that legal cost is a reflection of how the negotiation unfolds, not something you can or should eliminate.

3. Quality of Earnings Is an Investment in Certainty

Even when the buyer arranges and pays for their own Quality of Earnings (QofE) report, many sellers choose to fund a seller-side or pre-emptive QofE to control the narrative. On a $10 million deal, a typical seller-side QofE runs in the $30,000 to $50,000 range.

Why do it? A good QofE can validate the earnings picture that buyers will scrutinize anyway. It helps you find and repair reporting issues before they become renegotiation points. It gives confidence to buyers early. It keeps valuation momentum going. But, most importantly, it avoids surprises. A surprise in diligence almost always costs more than the money you’d spend to avoid it. If your anticipated transaction value is less than $10 million, then I recommend looking at the number and nature of your add-backs or normalization adjustments and determine if it truly warrants an outside firm taking a look. If all you are adding back is your salary, benefits, and cell phone, a sell-side QofE won’t pay for itself.

4. Accounting and Tax Advisors Keep You Out of Trouble

A lot of people think accounting and tax advisory costs only matter if there’s a problem. That’s not true. These advisors help structure the deal in tax-efficient ways, calculate working capital adjustments, allocate purchase price for tax purposes, and help coordinate final filings.

For a $10 million deal with relatively clean books, these services often cost $20,000 to $40,000. That may feel like a lot when compared to your CPA’s usual annual bill, but this is specialized transaction work. Done right, good tax planning protects your net proceeds. Done poorly, or not at all, and you could leave money on the table or owe a surprise tax bill later. I especially recommend good tax advisors for C corp sellers who might be able to take advantage of Section 1202, or those who use PTET as a tax planning tool. A sale may alter how these are deducted.

5. Transaction and Retention Bonuses Reduce Scope for Regret

Once you reach the finish line, many deals also include transaction bonuses or stay bonuses for key employees or management. Buyers often use these to secure continuity. Sellers sometimes elect to fund them at close as part of deal dynamics or to reward those who have stayed by their side all these years.

On a $10 million deal, seven-figure employee bonus pools are rare, but four- or five-figure bonuses for critical players are not. In aggregate, it’s common to see $100,000 to $250,000 or more allocated for these incentives.

Sellers forget about this because it doesn’t appear on a spreadsheet labeled “fees,” but it absolutely comes out of the amount you walk away with because you won’t pay them until the deal actually closes.

6. Escrows and Holdbacks Affect Your Liquidity

Something else that impacts how much you take home is escrows and holdbacks. These aren’t fees paid to a third party, but they are portions of the purchase price that the buyer holds as security against indemnity claims or post-closing adjustments.

On a $10 million deal, that amount is often 5 to 10 percent of the purchase price held for 12 to 18 months. That’s $500,000 to $1 million sitting in escrow.

If it’s sitting in an escrow, you earn money on it. If it’s a holdback, you don’t. But in the end, you earned that money, the buyer acknowledges you earned it, but you can’t use it until the holdback period expires. If you’re thinking about buying a new home or starting a second act right after closing, you need to plan for the fact that a meaningful chunk of your proceeds is temporarily illiquid.

7. Tail Insurance Protects You After the Sale

One of the fees that often surprises sellers late in the process is tail insurance, sometimes referred to as D&O runoff coverage. This extends your liability coverage after the deal closes so that claims tied to pre-closing conduct aren’t left uncovered. Many buyers of IT service businesses also require tail insurance for cyber security and employment practices.

Most buyers will require tail insurance. Most sellers pay for it, unless you negotiate otherwise in your LOI. On a $10 million deal, this insurance often costs in the $20,000 to $50,000 range depending on coverage limits and term length.

Sellers don’t like this because it doesn’t feel like a negotiated term; it feels like a cost you didn’t expect. It matters, though, because it is insurance against claims that could otherwise expose you personally after you’ve exited the business.

8. Post-Close Costs Show Up After the Champagne

Even after the deal is signed and the funds are wired, there are usually a few post-close advisory and cleanup costs. These include final tax filings, purchase price adjustments, escrow true-ups, and maybe some accounting wrap-up work.

In most $10 million deals I work on, this last phase adds $10,000 to $25,000 in costs before everything is truly finished.

It doesn’t happen on every deal, but it happens often enough that it should be included in your planning.

9. OPTIONAL – Equity Investment Is Not a Fee, But It Reduces Liquidity

Another item that can materially affect perceived proceeds is equity rollover or equity investment. On a $10 million deal, it is not unusual for a seller to reinvest 10 to 20 percent of the transaction value into the acquiring entity. Using a 15 percent example, that means $1.5 million of the purchase price is rolled into equity rather than taken as cash at close. This is not a fee and it is not money lost, but it does change liquidity. Sellers often underestimate the emotional impact of this because the headline number still says $10 million, even though only $8.5 million is paid in cash before fees, escrows, and adjustments. The tradeoff, of course, is potential upside. That $1.5 million equity position may be worth significantly more at a second exit, or it may take years to realize any return at all. The key is understanding that equity rollover affects timing and risk, not value, and making sure the remaining cash proceeds still meet your personal and financial goals at closing.

What This Actually Looks Like on a $10 Million Deal

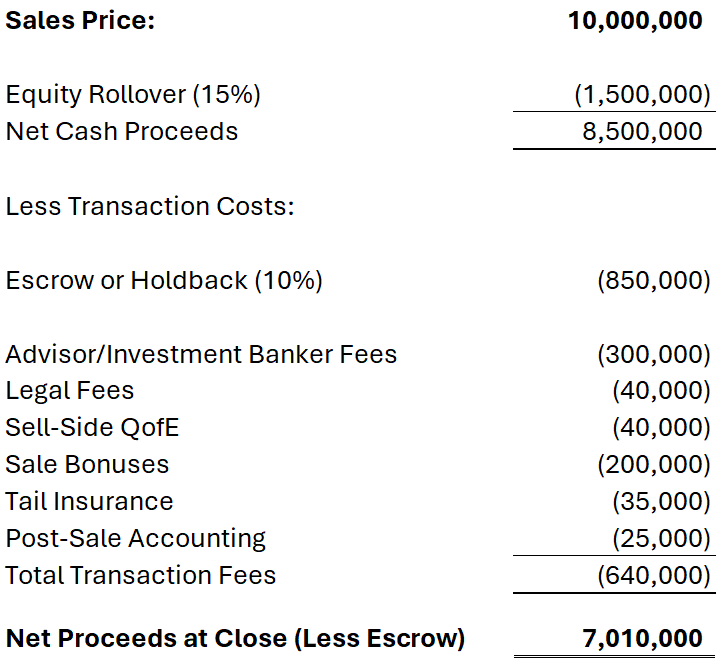

Let’s step back and look at the net effect of all of this. If you sold your company for $10 million with a 3 percent advisor fee, reasonable legal costs, a QofE report, tax planning, retention incentives, tail insurance, and post-close cleanup, your total transaction costs can easily land in the mid-six-figures ($640,000), assuming the return of all the escrow amounts.

These fees and costs add up. Then consider the escrow holdback that’s sitting in a third-party account for the next year or so. Here is an example of the net proceeds from a $10 million sale using the amounts we reviewed above:

If you focus on one number from the process – net proceeds after fees and costs – you’ll get a clearer, more realistic picture of what selling your business truly costs.

One Last Point Every Seller Should Know

Net working capital shortages are often misunderstood.

This is where things get confusing for many sellers. Most deals include a net working capital target, which is meant to ensure the business is delivered with a normal, ongoing level of operating liquidity. If, at close, the actual current net working capital is below that target, the seller typically owes the difference to the buyer. The reverse is also true, meaning if you deliver more net working capital than expected, that additional amount will be added to the purchase price.

Let’s use a real example:

Suppose that, at closing, the company’s current working capital is $40,000 less than the agreed working capital target. That shortage might feel frustrating, especially if you did nothing wrong. In many cases, it happens because sellers did a very good job collecting accounts receivable before close or they decided not to pay a few vendors early like usual and they kept the cash instead.

Here is the key point many sellers miss: that $40,000 is not lost money. It is a timing adjustment.

If you aggressively collected receivables before close, you likely harvested more cash than usual. In a company selling for $10 million, it is common for there to be $400,000 to $500,000 or more of excess cash on the balance sheet at close. That excess cash is typically distributed to the seller prior to the close.

So, while you may write a $40,000 check for a working capital shortfall, you are also walking away with several hundred thousand dollars of harvested cash that you would not have received otherwise. When viewed together, the economics usually favor the seller. The mistake is looking at the working capital adjustment in isolation instead of understanding how it interacts with cash at close.

The Real Lesson

On a $10 million deal, total transaction costs often land in the mid-six figures before considering escrow holdbacks. That is normal. It is not a failure of the process. It is the process.

The sellers who feel best at closing are not the ones who avoid these costs. They are the ones who understand them, plan for them, and see how the pieces fit together.

Selling your business is one of the most significant financial events of your life. The goal is not just a strong headline number. It is a result that feels right when the wires go out and the dust settles. That only happens when expectations meet reality.

Wise sellers recognize that it is not about avoiding fees. It is about managing them. When you understand the costs ahead of time, you make better decisions, prepare more effectively, and structure your deal in a way that protects what you keep.

A $10 million deal should feel like freedom. I want you to walk away feeling like it was worth it, not surprised by the costs that showed up at the finish line.

If you want to maximize what you take home when you sell your business, planning and preparation matter just as much as valuation. Let’s make sure your exit is both successful and satisfying.

* I’ve used a $10M amount because it is easy to calculate percentages. Many of our sellers sell for much, much more!

Should You Buy a Business Before Selling Your Own?

Should You Buy a Business Before Selling Your Own?